Learn all about superior mesenteric artery syndrome symptoms and treatment. Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is also known as Wilkie syndrome.

SMA syndrome was first described in 1861 by Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky in victims at autopsy, but remained pathologically undefined until 1927 when Wilkie published the first comprehensive series of 75 patients. According to a 1956 study, only 0.3% of patients referred for an upper-gastrointestinal-tract barium studies fit this diagnosis, making it one of the rarest gastrointestinal disorders known to medical science.

Nonetheless, the entity (also called cast syndrome) is a well-known complication of scoliosis surgery, anorexia, and trauma. It often poses a diagnostic dilemma; its diagnosis is frequently one of exclusion. The patient often presents with chronic upper abdominal symptoms such as epigastric pain, nausea, eructation, voluminous vomiting (bilious or partially digested food), postprandial discomfort, early satiety, and sometimes, subacute small bowel obstruction. Symptoms of superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome often develop from 6-12 days after scoliosis surgery.

Delay in the diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome can result in malnutrition, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, gastric pneumatosis and portal venous gas, formation of an obstructing duodenal bezoar, hypovolemia secondary to massive GI hemorrhage, and even death secondary to gastric perforation.

Medical therapy usually begins with the initiation of intravenous fluids and, once no significant emesis, with the frequent administration of small amounts of liquids. In some cases, nasojejunal or nasogastric tube feedings with a standard liquid diet may be indicated. If the patient is completely obstructed or unable to tolerate liquids, total parenteral nutrition is indicated.

Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome (SMAS)

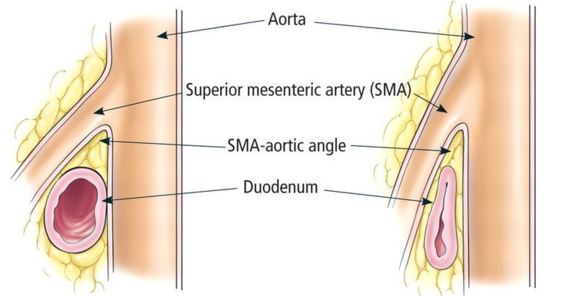

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS) is a digestive condition that occurs when the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine) is compressed between two arteries (the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery). This compression causes partial or complete blockage of the duodenum. This rare, potentially life-threatening syndrome is typically caused by an angle of 6°–25° between the abdominal aorta and the SMA, in comparison to the normal range of 38°–56°, due to a lack of retroperitoneal and visceral fat (mesenteric fat). In addition, the aortomesenteric distance is 2–8 millimeters, as opposed to the typical 10–20. However, a narrow SMA angle alone is not enough to make a diagnosis, because patients with a low BMI, most notably children, have been known to have a narrow SMA angle with no symptoms of SMA syndrome

Superior Mesenteric Artery

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is one of the three non-paired arteries that provide blood to the midgut and other abdominal viscera. The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) arises from the anterior surface of the abdominal aorta, just inferior to the origin of the celiac trunk, and supplies the intestine from the lower part of the duodenum through two-thirds of the transverse colon, as well as the pancreas.

SMA syndrome Symptoms

Symptoms vary based on severity, but can be severely debilitating. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, fullness, nausea, vomiting, and/or weight loss. Some symptoms are;

- Feeling full quickly when eating

- Bloating after meals

- Burping (belching)

- Nausea and vomiting of partially digested food or bile-like liquid

- Small bowel obstruction

- Weight loss

- Mid-abdominal “crampy” pain that may be relieved by the prone or knee-chest position or by lying on the left side

- “Food fear” is a common development among patients with the chronic form of SMA syndrome.

For many, symptoms are partially relieved when in the left lateral decubitus or knee-to-chest position, or in the prone (face down) position. A Hayes maneuver (pressure applied below the umbilicus in cephalad and dorsal direction) elevates the root of the SMA, also slightly easing the constriction. Symptoms can be aggravated when leaning to the right or taking a supine (face up) position. Other complications that may arise in people with SMAS include:

- Other electrolyte imbalances

- Malnutrition

- Hypotension

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Aspiration pneumonia

SMA syndrome Radiology Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of SMA syndrome is based on clinical symptoms and radiologic evidence of obstruction.

- Plain radiograph dilated fluid and gas-filled stomach and proximal duodenum.

Upper GI fluoroscopy can demonstrate dilatation of the first and second part of the duodenum, extrinsic compression of the third part, and a collapsed small bowel distal to the crossing of the SMA. - CT and magnetic resonance angiography (CTA/MRA) enable visualization of vascular compression of the duodenum and measurement of aortomesenteric distance normally, the aortomesenteric angle and aortomesenteric distance are 25-60° and 10-28 mm, respectively in SMA syndrome, both parameters are reduced, with values of 6° to 15° and 2 to 8 mm.

SMA syndrome Treatment

- Superior mesenteric artery syndrome treatment typically focuses on addressing the underlying cause of the condition.

- Nasogastric decompression (a tube passed through the nose into the stomach) and proper positioning after eating (such as lying in the left side or standing or sitting with a knee-to-chest position) may be recommended to alleviate symptoms.

- In severe cases, intravenous (IV) nutritional support and/or a feeding tube may be needed to provide enough calories.

- Metoclopramide treatment to avoid vomiting may be beneficial for some people.

Surgery may be needed if other treatment strategies do not work. However, other treatment options should usually be tried for at least 4-6 weeks before considering surgery. - Surgery options are:

- Strong’s procedure: Where the duodenum is re-positioned to the right of the superior mesenteric artery

- Gastrojejunostomy: Where the jejune (the part of the intestines that continues with the duodenum) is joined directly to the stomach

- Duodenojejunostomy with or without resection of the fourth part of duodenum.

Health & Care Information

Health & Care Information