The most prevalent type of gynecological tumor is leiomyoma. Thirty percent to fifty percent of reproductive-age women are affected by them, and they are most common in people of African origin. Myometrial contractions during labor and menstruation cause a thickening of the myometrium, the central layer of the uterine wall, and the development of benign tumors called leiomyomas. As a consequence of this, leiomyomas are associated with an increased probability of infertility, miscarriage, and other complications during pregnancy.

Fibroids of the uterus are benign growths that commonly manifest throughout a woman’s reproductive years. Uterine fibroids, also known as leiomyomas or myomas, seldom progress to cancer and are not linked to an elevated chance of uterine cancer.

Leiomyomata of the uterus mostly range in size from a little, barely noticeable tumor to a large, palpable tumor, depending on where in the uterus they are located. In extremely rare situations, a uterine myoma develops into a malignant sarcoma (leiomyosarcoma). Fortunately, there is no increased risk of malignant transformation when there is a cluster of many leiomyomas.

Leiomyomatous Uterus Symptoms

The majority of uterine myomas are asymptomatic and do not require treatment, despite their frequency. Asymptomatic uterine leiomyomas need to be treated if the uterus is too big, the ovaries are hard to reach, estrogen replacement is hard, or the size of the uterus changes quickly. Leiomyomas often cause menorrhagia, pelvic pain or pressure, and problems with reproduction. Menorrhagia is the most frequently observed symptom of leiomyomas. Unknown factors are responsible for menorrhagia in leiomyomas.

Although rectal symptoms are uncommon in this scenario, inflammation or blockage of the rectum or rectal sigmoid often takes place. Acute pain accompanied by a low-grade temperature and uterine soreness is associated with the development of leiomyomas, torsion, or pedunculated subserous myoma.

There is a link between being childless and the frequency of fibroids. As the number of pregnancies carried to term increases, so does the woman’s relative protection against developing fibroids. When compared to a nulliparous woman, a woman who has five-term pregnancies possesses a 25% lower incidence of leiomyoma.

Leiomyomatous Uterus Causes

Genetic mutations in smooth muscle cells are a major cause of Leiomyomatous Uterus. In addition, the female steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone are linked to an increased risk of fibroid growth due to the effect that these hormones possess on cell division and the increase in particular growth factors that they cause. The chance of developing leiomyomas, therefore, increases with the quantity of these hormones.

Breastfeeding, perimenopause, and pregnancy are related to elevated levels of female steroid hormones. Fibroid development is also affected by substances like insulin-like growth factors that assist the body to maintain tissues.

ECM, or extracellular matrix, is the glue that holds cells together. It’s like the mortar between bricks in a wall. ECM is higher in fibroids, which makes them hard. ECM not only alters the biology of the cells but also stores growth factors.

According to medical professionals, stem cells in the uterus’s smooth muscle tissue are the source of uterine fibroids (myometrium). An individual cell eventually develops a solid, rubbery mass that is unique from neighboring tissue after dividing numerous times.

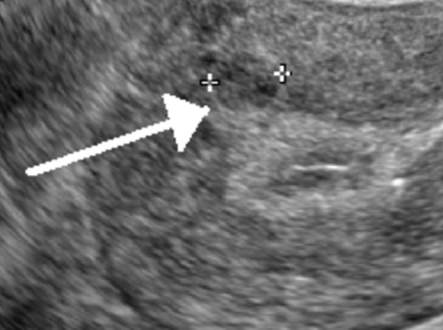

Leiomyomatous Uterus Ultrasound

The most effective way to image uterine fibroids is through transvaginal ultrasonography. When it comes to the diagnosis of this disease, its detection sensitivity ranges somewhere between 90 to 99 percent. Saline-infused sonography is an advancement in ultrasound technology that increases the sensitivity of the test for detecting subserosal and intramural fibromas. Fibroids look like a firm, well-defined, hypoechoic mass. Ultrasound examinations in these areas typically reveal varying degrees of shadowing and echogenicity distortion from calcifications or necrosis.

Leiomyomatous Uterus Treatment

The treatment of uterine leiomyomas sometimes referred to as uterine fibroids, ought to be individualized for each patient. When developing a treatment plan, it is essential to take into account the tumor’s size, location, symptoms, the patient’s age, and his or her goal to preserve fertility.

Leiomyomas that are asymptomatic are typically not treated. However, non-invasive procedures that induce the leiomyoma to shrink are often used to eradicate the tumor and alleviate the symptoms it causes in patients. Such procedures include uterine artery embolization and MR-guided targeted ultrasound surgery. If these measures are ineffective, a hysteroscopic or abdominal myomectomy, or even whole uterine excision, becomes necessary (hysterectomy). The decision between the two options frequently comes down to whether the person wants to keep their fertility.

Medications are available to alleviate symptoms. In cases of heavy or protracted menstruation, oral contraceptives are given. To shrink the tumor and shorten the surgical procedure, recovery period, and blood loss, the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are also administered to patients who are nearing menopause or before surgery. Long-term use of GnRH agonists often results in adverse effects such as the appearance of menopausal symptoms.

Health & Care Information

Health & Care Information